As discussed in the previous part, formal grammars can be used to generate and manipulate text strings.

The question is how this can be extended to generate pictures, movies, or music.

One possibility would be to interpret the symbolic output as some sort of representation or encoding, which could be unfolded to create the final output.

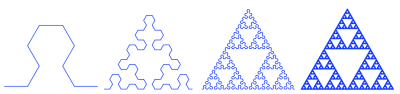

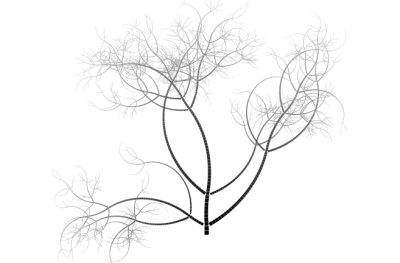

For instance it would be rather simple to create a grammar, which created an SVG XML file for output. A wide used example of this approach is Lindenmayer systems, where the output is interpreted as a sort of ‘LOGO Turtle Graphics’.

Lindenmayer Systems

Lindenmayer Systems (or simply L-systems) are related to formal grammars, but in contrast to formal grammars which describe the syntax for the infinite number of sentences for a formal language, L-systems describe a generational process for manipulating text strings. They were used by Lindenmayer to simulate plant and tree growth.

In L-systems you iteratively apply all the production rules to the output of the previous iteration. L-systems do not have terminal symbols in the same sense as formal grammars do – so the expansion never stops. L-systems may, however, have optional constants which are not replaced and in this sense acts a bit like terminal symbols. In contrast to formal grammars, L-systems are not expected to terminate with a string of constants, they will keep on ‘growing’. Since the expansion never stops, L-systems are usually calculated for a given number of generations.

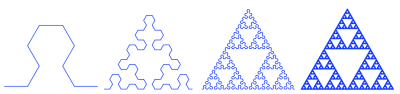

An example L-system:

A-> B-A-B

B-> A+B+A

Starting with the symbol ‘A’, this system would yield the following expansion: A, B-A-B, A+B+A-B-A-B-A+B+A, …., and so forth. Notice the difference to formal grammars: if these were production rules in a formal grammar, ‘B-B-A-B-B’ would be a valid sentence: this is not the case for L-systems, since all rules must be applied at each step.

The way L-system traditionally are used for generative purposes is by applying geometric semantics to the output: for instance, we could interpret A and B as moving one step forward, and + and – as turning 60 degrees clockwise or counter-clockwise. With this interpretation we get the following output:

– a fractal Koch curve.

‘The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants’ by Prusinkiewicz and Lindenmayer describes L-systems in details and is now available for free at Algorithmic Botany.

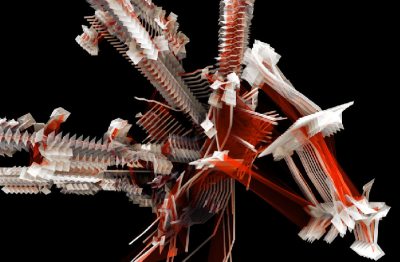

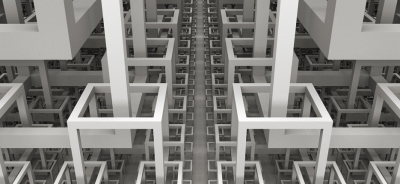

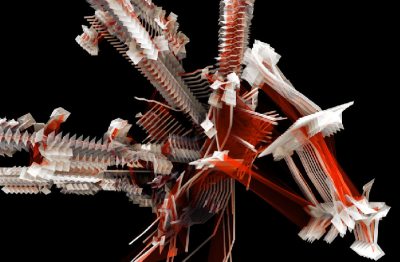

At this point I must admit that I always found L-systems to be quite dull and boring. Usually texts about L-systems are accompanied by Koch or Dragon curves and one or more simple plant or tree structure. However recently I stumbled upon this site: L-systems in Architecture by architect Michael Hansmeyer. Some of his creations are stunning, and the presentation is excellent, complete with step-by-step animations.

(Example image from L-Systems in Architecture.)

Context Free Design Grammar

In L-systems the symbol generation and the geometrical interpretation are two independent steps.

A perhaps more interesting approach is to embed the geometry inside the production rules. This requires a slight extension to the formal grammars.

Chris Coyne created the Context Free Design Grammar, which just like a formal grammar has production rules and non-terminal and terminal symbols – though it only has three terminal symbols: the ‘circle’, ‘square’ and ‘triangle’ geometrical primitives.

The Context Free Design Grammar extends the syntax of the formal grammars by including transformation operators (which are called ‘adjustments’ in CFDG terms). These transformation operators modify the current rendering state. Notice that while (rendering) states are being introduced in the CFDG, the actual expansion of a non-terminal symbol is still context-free. The CFDG also allows different weights to be assigned to each production rules.

Mark Lentczner and John Horigan created a cross-platform (Windows/Mac/Linux) graphical front-end simply called Context Free for CFDG. It is a wonderful little application – it is very easy to use and play around with.

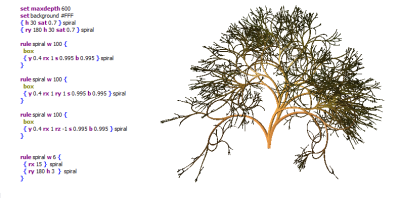

Here is an example of CFDG code:

startshape SEED1

rule SEED1 {

SQUARE{}

SEED1 {y 1.2 size 0.99 rotate 1.5 brightness 0.009}

}

rule SEED1 0.04 {

SQUARE{}

SEED1 {y 1.2 s 0.9 r 1.5 flip 90}

SEED1 {y 1.2 x 1.2 s 0.8 r -60}

SEED1 {y 1.2 x -1.2 s 0.6 r 60 flip 90}

}

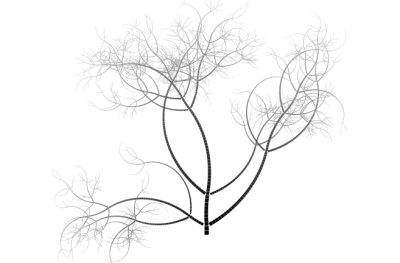

yielding the following output:

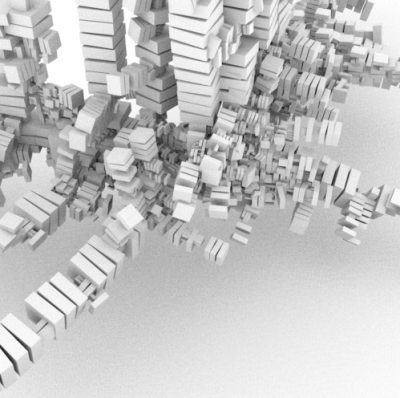

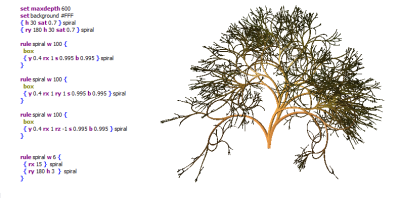

EisenScript and Structure Synth.

After I discovered Context Free I decided that I wanted to create a similar program for 3D geometry, a project that turned into the Structure Synth application.

In order to describe a grammar for 3D modelling I had to alter the CDFG syntax a little, which resulted in the EisenScript used in Structure Synth (named after the Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein).

I deliberately chose a new name, since I was not sure that the EisenScript was going to be a context free grammar – being slightly more pragmatic, I wanted to sacrifice the purity of CDFG for having more control over the graphical output. In particular, I added the possibility of ‘retiring’ rules: after a rule has reached a certain recursive depth, it can either be terminated or substituted by a new rule. (Actually I am a little in doubt, whether this ‘retiring’ is just a form of shorthand notation for specifying something which would be possible to express in a context free grammar). This ‘retiring’ rule makes it possible to create structure like a Menger sponge.

Also a few other alterations of CFDG were made:

The ‘startrule’ statement: in CFDG startrules are explicitly specified. In EisenScript, a more generic approach is used: statements which can be used in a rule definition, can also be used at the top-level scope. What actually happens is that Structure Synth collects everything at the top-level scope and creates an implicit start rule.

Termination criteria: in CFDG recursion automatically terminates when the objects produced are too small to be visible. This is a very elegant solution, but it is not easy to do in a dynamic 3D world, where the user can move and zoom with the camera. Several options exist in Structure Synth for terminating the rendering.

Transformation order: in CFDG transformations (which CFDG refers to as adjustments) in curly brackets are not applied in the order of appearance, and if multiple transformations of the same type are applied, only the last one is actually carried out. For transformations in square brackets in CFDG the order on the other hand is significant. In Structure Synth the transformation order is always significant and no transformations are omitted: transformations are applied starting from the right-most one. Also in CFDG the transformation are specified after the rule call, in EisenScript they must appear before the rule call.

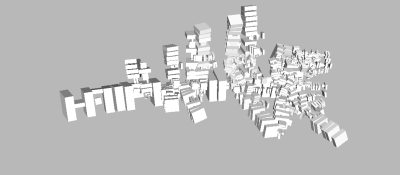

An EisenScript program similar to the one above would look like this:

EisenScript example (click to enlarge)

Of course there are also other obvious differences between CFDG and EisenScript: the transformation rules were altered to new 3D equivalents, and a new set of primitives were chosen. (Take a look at the EisenScript Reference for more details.).

Differences to procedural programming

An EisenScript grammar like the one above looks a lot like a ‘normal’ computer program – the syntax is actually quite close to the syntax of procedural programming languages like C, Java, Pascal, or Basic. And instead of thinking of EisenScript as a grammar and its output as sentences in the language specified by this grammar, it is perhaps easier to think of EisenScript as an ordinary computer language.

The similarities may be a bit deceptive though, since there are two major differences: functions (which are the rules in EisenScript) may have multiple definitions each with a arbitrary weight. And recursion is handled ‘breadth first’.

The last point requires an explanation: Whenever a procedural programming language executes a function or procedure, it does so in sequential order – the individual statements in the function are executed in the order of appearance. If one of the statements is a procedure call, this procedure is executed and must be completed before the next statement is executed. The state of the currently executing function (the return address pointer, local variables, …) are stored in stack frames on a call stack, in order to be able to return after executing a function. Put differently, this means the function call tree for the program is traversed ‘depth-first’.

Recursion in Structure Synth is handled differently. Instead of a call stack, there is generational stack: whenever a rule is encountered, all sub rules and primitives in the rule definition are pushed onto a new stack that will be evaluated at the next generation. This means the rules are traversed ‘breadth first’ – all calls at the same recursive depth are processed at the same time.

Consider the following example:

Procedure recurse() {

recurse(); // call myself

another(); // call another function

}

A traditional programming language would never reach the ‘another()’ function. It would recurse until the call stack overflowed. In contrast, In Structure Synth the first generation would process both the ‘recurse’ and ‘another’ statement. (When processing the ‘recurse’ statement it would schedule new ‘recurse’ and ‘another’ calls for the next generation).

Well, this concludes part II.

Part III will describe other grammar approaches to generative art and procedural modelling: namely Style Grammars and Shape Grammars.